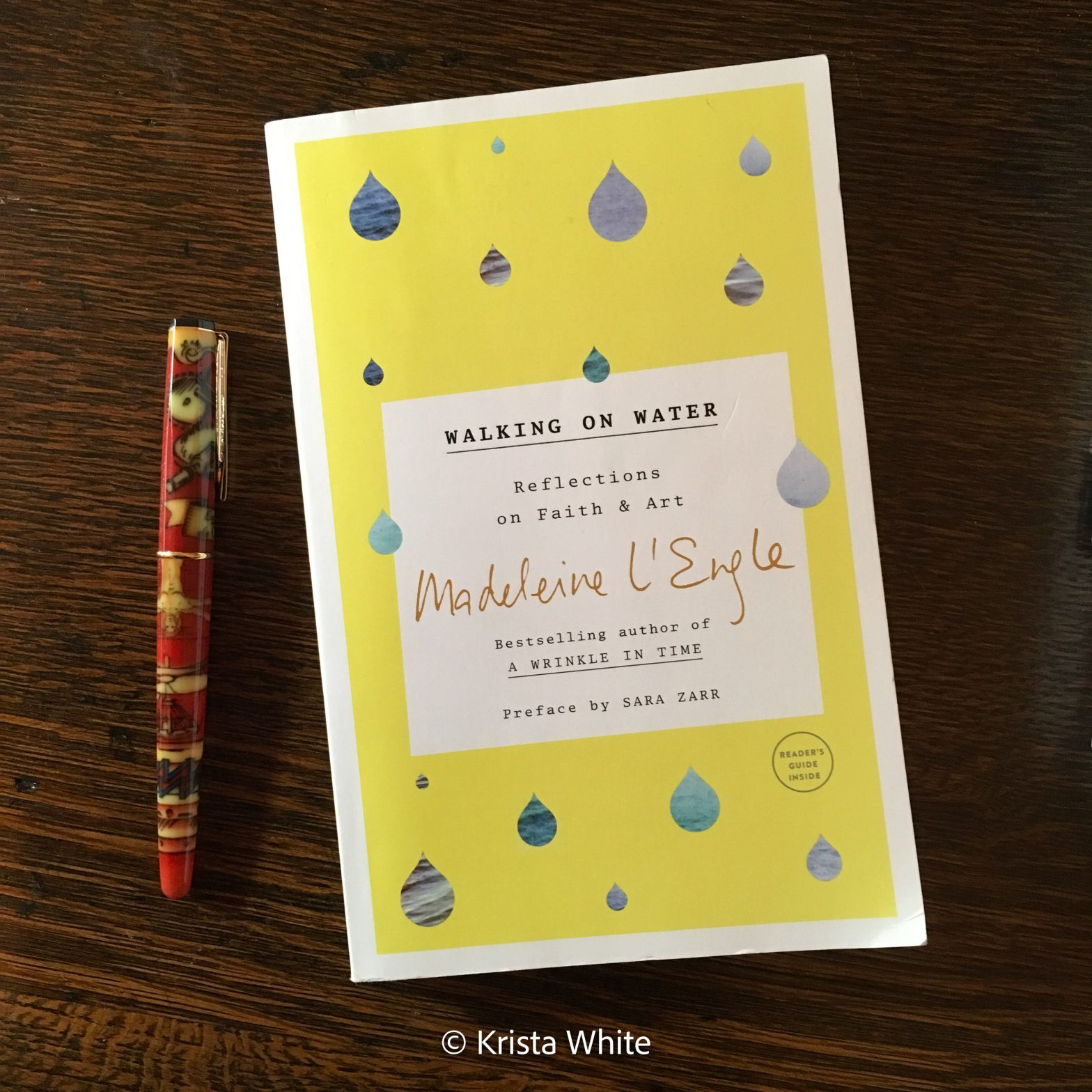

I didn’t read Walking on Water because it was written by a woman. (Not all women can write well.) And I didn’t read it because it was a Christmas gift. (Though, I did pick it out.) I opened it to page one (not big on introductions, I confess) and began to read because I liked the cover. The title on the cover had something to do with it: Walking on Water. And, of course, the subtitle was what really interested me: Reflections on Faith & Art.

As a writer and a Christian, I needed to be inspired. I needed to have some light put on the chaos that my current book project seemed to be hurriedly devolving into. It was just mental fatigue in the end, thankfully. But I am grateful to Madeleine L’Engle (God rest her soul) for handing me a flashlight in the dark. This collection of essays on the relationship between faith and art is a gem for any creative.

Best known for her science fiction book A Wrinkle in Time (which I have yet to finish reading), L’Engle offers some out-of-the-box ways of thinking about time and the Creation. The mysterious story of NASA astronauts hearing a live radio program transmitted in the 1930s (not a recording) is alone worth buying the book.

L’Engle loves the inexplicable and that makes her not your typical “Christian writer.” She actually didn’t like such names or labels. Not that she wasn’t a convinced believer and devout in her obedience to Jesus. She asserts that such labels as “Christian artist” or “Christian writer” are unnecessary because art is only art when it communicates meaning. This is the message of Christianity. It gives life meaning.

Borrowing from Leonard Bernstein’s statement that music is “cosmos in chaos,” L’Engle states:

“It is true not only of music; all art is cosmos, cosmos found within chaos…[A]ll Christian art (by which I mean all true art) is cosmos in chaos.”

L’Engle’s pursuit of cosmos in her art took her on many journeys into the abyss of doubt. Artists, like all true scientists, must ask cosmic questions and not be afraid of the answers. Imagination was L’Engle’s vehicle of exploration to the outreaches of the universe and where her own creativity could take her. And she encourages all artist to learn “the faithfulness of doubt” which is a “prerequisite for a living faith” and the basis for the creation of true art.

“Love, not answers,” L’Engle writes. “Love, which trusts God so implicitly despite the cloud (and is not the cloud a sign of God?), that it is brave enough to ask questions, no matter how fearful.”

Throughout the book, L’Engle quotes from her notebooks, which she has filled with reflections and thoughts from other artists and thinkers. To conclude, I’ll throw out a few of these nibbles of wisdom in the hopes that they’ll work on you like the cover’s bright yellow did to me and lure you into getting the book and reading it until your brain pops with excitement to create something good.

“an abstract composition by Kandinsky or van Gogh’s landscape of the cornfield with birds…is a real instance of divine transfiguration, in which we see matter rendered spiritual and entering into the “glorious liberty of the children of God.” This remains true, even when the artist does not personally believe in God. Provided he is an artist of integrity, he is a genuine servant of the glory which he does not recognize, and unknown to himself there is “something divine” about his work. We may rest confident that at the last judgment the angels will produce his works of art as testimony on his behalf.” —the Rev. Canon A.M. Allchin, of Canterbury Cathedral, England

“You should utter words as though heaven were opened within them and as though you did not put the word into your mouth, but as though you had entered the word.” —Martin Buber

“You must once and for all give up being worried about successes and failures. Don’t let that concern you. It’s your duty to go on working steadily day by day, quite quietly, to be prepared for mistakes, which are inevitable, and for failures.” —Anton Chekov

“The thought that I must, that I ought to, write, never leaves me for an instant.” —Anton Chekov